For the past one and a half years, I have been using the Zettelkasten method for note-taking. For those of you who are unaware, Zettelkasten is a note-taking method popularized by German sociologist Niklas Luhmann. It promises to help you learn, study, research, and think better. This note-taking method will efficiently turn your thoughts and discoveries into convincing written pieces.

I learned about this method from various blog posts back in 2018. I thought that the technique was terrific and started using it immediately. At that time, I was using Bear App. Bear supported markdown editing and linking from one note to another, which is one of the critical points of the whole methodology. When I started learning, the advice was to start making notes and making connections among them. So admittedly, my knowledge of the method is quite shaky. It was a lot of trial and error.

I found out, later on, that there was a book titled "How to take smart notes" written by Sönke Ahrens that explained this note-taking method in depth. I read this book in 2019. I really should have read this book earlier. This book gives me lots of good advice on properly setting up and using the Zettelkasten method for note-taking.

Here are the three important lessons I have learned while using this note-taking method over the years.

Do not put everything in a single system

In the beginning, I put everything in one single app. At the time, I was using Bear App. And I use tags to differentiate between my ordinary notes and slip-box notes. This was fine for a while. At some point, I even added my productivity system (to-do list, plan, etc.) into this one application.

But then I notice that I don't actually get more value from this note-taking system. When I need to search for something, there will be way too many results coming back at me. And some of them are highly irrelevant, a to-do task, a web clip reference, a highlight from a book, and so on.

I felt that I needed to put my slip-box into its own system. Making a clear line between my own thoughts and ideas from the rest of the world. And having everything in a single system prevents me from achieving that. I mean, do I know about something, or do I know something? Is my knowledge fake knowledge? Have I fallen into the collector's fallacy? I always have these questions. So this is why I no longer put everything in a single app.

Ahrens warns explicitly that the slip box should not be about collecting.

The idea is not to collect, but to develop ideas, arguments and discussions.

According to Sönke Ahrens, the setup of Zettelkasten is divided into four components. The slip-box where you put what he calls permanent notes and an editor. Something to capture ideas (fleeting notes) with. A reference management system to collect the references and your notes during your reading (literature notes).

In other words, he suggests that you use different tools for these functions. A pen and paper for fleeting notes. A reference manager to store literature notes. A slip-box to keep permanent notes after processing the fleeting and the literature notes.

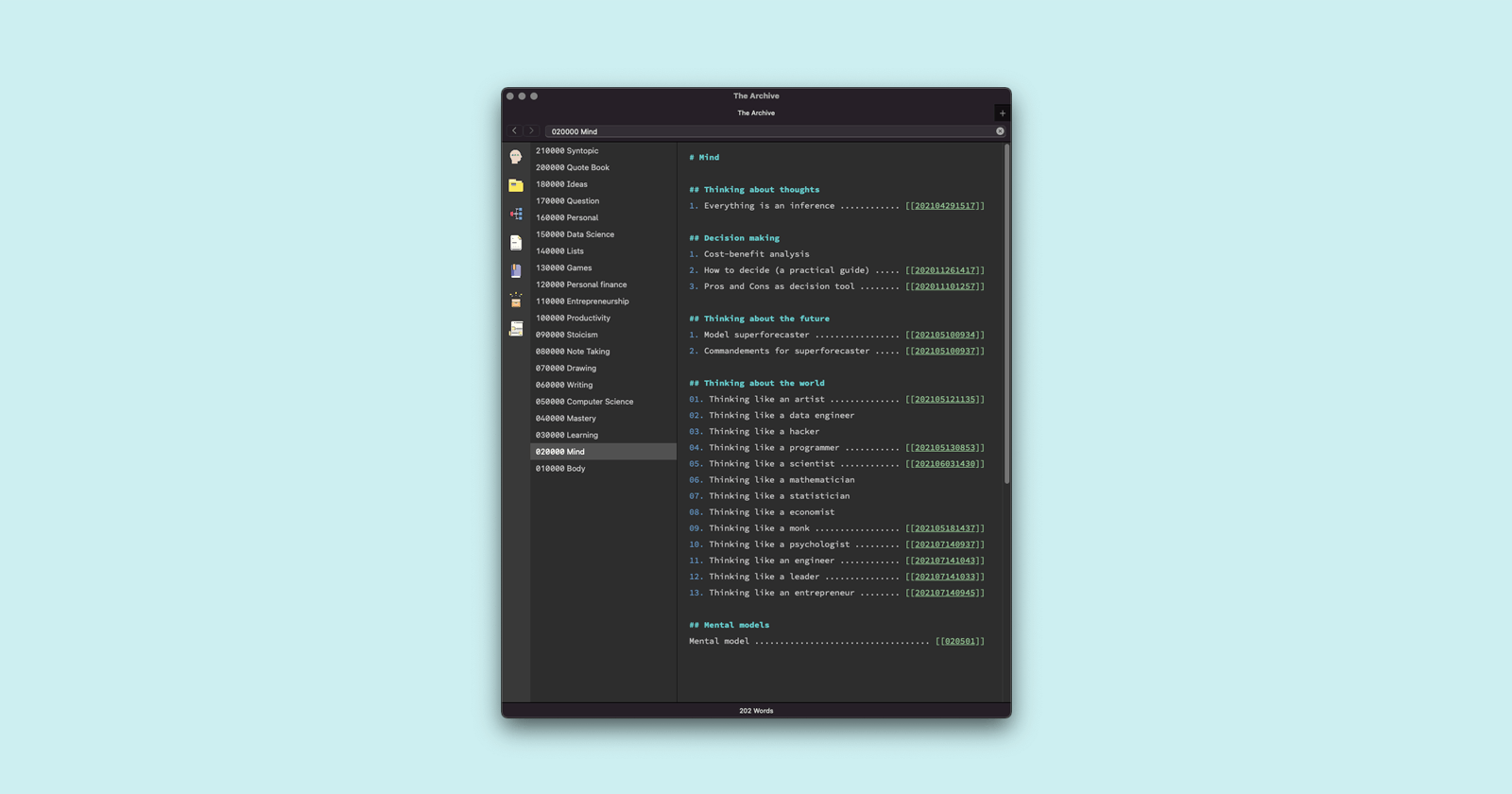

Rely on index

Once I get to a certain number of notes (600-700 notes), I feel I can't keep up with my slip box. Searching for tags or keywords returns too many results. At this point, to help me organize my slip box, I used the index. This comes out naturally, but as I later learn, I am not the only one struggling to keep up with all the notes I have taken. In the book "How to take a smart note," Ahrens, when describing the elements of the Luhmann system, said:

The last element in his file system was an index, from which he would refer to one or two notes that would serve as a kind of entry point into a line of thought or topic. Notes with a sorted collection of links are, of course, good entry points.

And further, when adding notes to the slip-box, he said:

- Now add your new permanent notes to the slip-box by: .... c). Making sure you will be able to find this note later by either linking to it from your index or by making a link to it on a note that you use as an entry point to a discussion or topic and is itself linked to the index.

This might remind you of a table of contents because it is a table of contents.

Soon after, I organized this further into topic and sub-topic, which is just an index of indexes. Later, I learned about the term "map of concepts," which is way cooler than topic and sub-topic.

I rely heavily on this topic, sub-topic, and index set up to help me find, connect and make sense of the notes. Every time I add a new note, I put a link from the index to the new note.

Use pen and paper for capturing ideas

There are many known benefits of note-taking with pen and paper. It helps you remember things. It makes you more active and creative. It helps you focus and avoid distractions. In fact, in a paper published in the journal Psychological Science, two US researchers claim that note-taking with a pen gives students a better grasp of the subject.

For the scientists, the reason is clear: those working on paper rephrased information as they took notes, which required them to carry out a preliminary process of summarising and comprehension; in contrast, those working on a keyboard tended to take a lot of notes, sometimes even making a literal transcript, but avoided what is known as "desirable difficulty. [1]

More and more, I rely on pen and paper to capture ideas. Every time I learn or read about a subject, I write them down in my A5 notebook. I utilized several note formats according to the content. Note-taking with a pen and paper has helped me ensure that I understand the topic, use my own words, and see the relationship between ideas before I put it in my slip-box. I find out the quality of my slip-box content is better when I do this.